Location: Home >> Detail

TOTAL VIEWS

Crop Breed Genet Genom. 2026;8(1):e260003. https://doi.org/10.20900/cbgg20260003

1 ICAR-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, Pusa, New Delhi 110012, India

2 ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi 110012, India

3 ICAR-Indian Agricultural Statistics Research Institute, New Delhi 110012, India

4 The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, India Office, New Delhi

* Correspondence: Vinod K. Sharma

#Contributed equally.

Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) is a widely cultivated and consumed Solanaceous crop, valued both as a vegetable and a spice, primarily because of its characteristic pungency. Capsicum species exhibits remarkable morphological variability, particularly in fruit shape, color, size and pungency levels. In the present study, 470 Capsicum annuum germplasm selections were comprehensively characterized using 18 agro-morphological traits. Multivariate statistical techniques including correlation analysis, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) were employed to assess genetic diversity. PCA revealed that the first three principal components accounted for substantial 81.4% of the total phenotypic variation. Fruit girth, fruit diameter, days to 50% flowering and days to first fruiting were identified as the major contributors to this variability. Correlation analysis revealed significant associations between various traits, while HCA grouped the 470 genotypes into four distinct clusters. The results highlight the extensive genetic diversity present within the C. annuum germplasm. The characterization data generated in this study provide valuable insights for the identification of superior lines and will be instrumental for further chilli breeding programmes, new variety development and overall crop improvement efforts.

Chilli peppers (Capsicum spp.) are a highly diverse group within the family Solanaceae. These chillies exhibit wide morphological variation in plant type, fruit shape, fruit colour, and pungency. As predominantly cross-pollinated species, chillies possess a genome size of approximately 3.5 Gb [1]. Originating in south and Central America, chillies have since spread globally and are cultivated across many countries. The name Capsicum is derived from the Greek term ‘kapsimo’ meaning 'to bite' [2]. The genus Capsicum comprises 43 species. Among these, five are domesticated: Capsicum annuum (L.), C. chinense (Jacq.), C. frutescens (L.), C. baccatum (L.), and C. pubescens (Ruiz and Pav.). Capsicum annuum is the most widely cultivated species worldwide [3]. Many varieties of chilli are valued for their pungency making both fresh and dried fruits important culinary spices. Green chillies are commonly used in chutneys and curries, while red chillies widely used as a flavouring agent. Mildly pungent and highly pigmented types, such as paprika, are widely used for color extraction. Beyond their culinary uses, capsaicin and its analogues have been associated with various medical benefits [4].

Chilli is a high-value horticultural crop with significant market demand and economic value, largely due to its unique pungent characteristics [5]. Consistently strong consumer demand further underscores its importance as a major horticultural crop [6]. As a high-value crop, chilli farming offers substantial benefits, mainly for small-scale farmers, thereby improving their financial and social status [7]. India is the world’s largest producer, consumer, and exporter of chilli pepper. In 2020-21, green chilli was cultivated over 0.411 million hectares, yielding 4.363 million metric tons, while dried chilli covered 0.702 million hectares with a production of 2.049 million metric tons (https://www.agricoop.gov.in).

Genetic variation within genetic resources is fundamental to successful crop improvement programmes [8,9]. In spite of the rich genetic diversity conserved in Capsicum spp., much of the germplasm and its derived selections remain underutilized; hence, comprehensive agro-morphological characterization is urgently required. Such characterization of chilli accessions provides valuable insights into a wide range of plant growth, flowering, and fruit-related traits [10]. Due to their often-cross-pollinated nature chilies exhibit wide genetic variation in both quantitative and qualitative traits [11]. Descriptors related to floral morphology and fruit characteristics, and growth habits, are vital for identifying variability within and between chilli species and for linking these traits to key biochemical and genetic traits [12]. For instance, fruit color is a critical trait determining chilli pepper fruit quality, as pigment composition is closely associated with flavor, nutritional value, and health benefits [13]. The mature fruit color of pepper is influenced by the relative concentrations of pigments like anthocyanin, carotene, and chlorophyll [14]. Moreover, genotypes exhibiting yellow coloration and pendant fruiting habit have been reported to possess higher vitamin C content [15]. Agro-morphological characterization serves as a vital link between the conservation and utilization of chilli germplasm by enabling the effective use of genetic diversity for crop improvement [16]. It also aids in the identification of duplicate accessions within germplasm collections, thereby enhancing genebank management efficiency [17]. Given the extensive data generated during germplasm characterization and evaluation, multivariate statistical analysis is particularly useful for informed decision-making in conservation and crop improvement programmes [18]. Among these techniques, principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) are commonly employed. While HCA classifies genotypes based on their overall similarity, PCA reduces data dimensionality by summarizing variation across multiple correlated variables [19]. In this context, the present study aims to estimate the extent and structure of genetic diversity among chilli germplasm selections using both qualitative and quantitative agro-morphological traits, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of diversity patterns across the studied chilli genotypes.

A total of 470 diverse genotypes were selected from 3,000 chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) germplasm accessions that exhibited admixtures or distinct morphological characteristics. These genotypes were obtained from the National Genebank of India, located at the Indian Council of Agricultural Research-National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources (ICAR-NBPGR) in New Delhi. Three released varieties Pusa Jwala, Kashi Anmol, and LCA 620 were used as check.

Experimental SiteThe present study was conducted at the New Area Farm Experimental Fields of ICAR-NBPGR, New Delhi, during the Kharif season of 2023. The site falls within the Trans-Gangetic Plains agro-ecological region of northern India and experiences a climate characterized by monsoon-influenced humid subtropical to semi-arid conditions. The kharif cropping season extends from July to October, coinciding with the south-west monsoon. A standard package of agronomic practices was followed from sowing to harvesting. Pre-transplanting irrigation was provided to facilitate proper seedling establishment. Soil moisture was maintained throughout the crop growth period through an appropriate irrigation schedule. Weeding was carried out 25–30 days after transplanting.

Experimental DesignThe 470 chilli germplasm selections were characterized using an Augmented Block Design (ABD). Each block consisted of 47 genotype entries, with check varieties randomized within each block. Raised beds, 15 cm in height, were prepared for each genotype, with 25-30 cm wide channels provided for drainage and irrigation. Each bed measured 1 m in width and 20 m in length, and ten plants per accession were maintained. The beds were prepared, and the seedlings were successfully transplanted on 10 February 2023.

Nursery and Transplanting ManagementChilli seeds were sown in nursery trays containing a 1:1 mixture of topsoil and biochar, and maintained under greenhouse conditions. To promote uniform and healthy seedling growth, the seeds were regularly irrigated and managed following standard nursery practices. Six-week-old uniform and healthy seedlings were then selected from each genotype and transplanted into the main experimental field.

ObservationsData on 18 agro-morphological traits, consisting of ten qualitative and eight quantitative traits, were recorded using descriptors developed by the ICAR-NBPGR, the World Vegetable Centre, and the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI). The traits were recorded at different growth stages, including seedling, vegetative, inflorescence, and fruiting stages, following the standard descriptor guidelines for pepper species.

The quantitative traits recorded included days to 50% flowering (DFF), days to first fruiting (DTFF), pedicel length (PDL, cm), pedicel diameter (PDD, cm), fruit length (FL, cm), fruit diameter (FD, cm), fruit girth (FG, cm), and fruit weight (FW, g). The growth stages at which these traits were measured are detailed in Supplementary Table S1. These traits were measured using a digital vernier caliper, ruler, measuring tape, and electronic weighing balance.

The qualitative traits recorded included flower position (FP), corolla color (CC), anther color (AC), stigma exertion (SE), fruit shape (FS), fruit shape at pedicel attachment (SPA), neck at the base of the fruit (NBF), fruit shape at the blossom end (FSBE), fruit surface (FSRF), and fruit position (FRP). The descriptors and descriptor states for these qualitative traits are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical AnalysisThe agro-morphological data were subjected to comprehensive statistical analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) at p < 0.05, descriptive statistics (mean, range, standard deviation, standard error, coefficient of variation), and the computation of various genetic parameters, including phenotypic and genotypic coefficients of variation (PCV and GCV), heritability broad-sense (H2), and genetic advance as a percentage of the mean (GAM), were performed using the “Trait-Stats” tool integrated in RStudio R v4.4.1 [20].

Scatter plots and Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) between the quantitative traits were generated using the 'GGally' package [21] in R v4.4.1 [22]. At a significance level of p < 0.05, r < 0 indicated negative correlations, while r > 0 indicated positive correlations. Additionally, scree plots, principal component analysis (PCA), and cluster analyses were conducted using the “factoextra” and “FactoMineR” packages in R Studio (R v4.4.1) [20].

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for all eight quantitative traits revealed highly significant differences among the genotypes (p < 0.01), indicating substantial genetic variability in the experimental material (Table 1). Block effects were non-significant (p > 0.05) for all traits except fruit length, for which the block effect was marginally significant (p < 0.05). However, the magnitude of variation attributable to block for this trait was considerably lower than the variation explained by genotypic effects.

Flowering and Fruiting TraitsDescriptive statistics for the eight quantitative traits revealed substantial variations among all germplasm selections evaluated in the present study (Table 2). Mean values for all the traits are presented in Supplementary Table S3. Chilli germplasm selections CH132 Sel-1, CH219 Sel-1, CH854 Sel-1, CH854 Sel-2, and CH854 Sel-3 flowered 19 days after transplanting, and were identified as early flowering accessions. In contrast, CH880 Sel-1, which flowered in 56 days after transplanting, followed by CH751 Sel-1 and CH671 Sel-1, both requiring 49 days to reach 50% flowering, were categorized as late-flowering genotypes.

The mean number of days to 50% flowering across all accessions was 33.01 days, while the best-performing check, Pusa Jwala, recorded a mean of 35.3 days. Notably, 328 accessions flowered earlier than the check variety, indicating a high frequency of early-flowering genotypes within the collection.

Days to first fruiting (DTFF) ranged from 26.10 to 70.77 days, with a mean value of 40.38 days. CH219 Sel-1, CH344 Sel-1 and CH384 Sel-1, were the earliest to reach first fruiting, within 26 days. In contrast, CH411-A Sel-1 and CH880 Sel-1 were the latest, reaching first fruiting approximately 71 days after transplanting. The mean DTFF for the best-performing check, Pusa Jwala, was 44.4 days, and 392 genotypes fruited earlier than the check varieties.

Fruit CharacteristicsFruit length (FL) showed significant variability among the genotypes, ranging from 1.95 to 13.70 cm, with a mean value of 6.41 cm. The shortest fruits were observed in the CH479 Sel-3 (1.90 cm), CH490 Sel-1 (2.16 cm) and CH484 Sel-2 (2.23 cm). Conversely, the longest fruits were recorded in CH869 Sel-1 (13.70 cm), followed by CH191-A Sel-1 (13.57 cm), and CH399 Sel-2 (13.16 cm). Among the check varieties, LCA 620 exhibited the highest fruit length (8.08 cm), whereas Kashi Anmol recorded the lowest value (5.88 cm). Notably, 84 germplasm selections exceeded the fruit length of the highest-performing check, LCA 620.

The genotypes exhibited a wide range of fruit girth, varying from 1.29 to 10.97 cm, with a mean value of 3.57 cm. Among them, CH124 Sel-2 (1.57 cm) and CH106 Sel-2 (1.83 cm) and CH252 Sel-1 (2.07) showed the smallest fruit girth, while CH430 Sel-1 (10.89 cm), CH869 Sel-1 (8.47 cm) and CH430 Sel-2 (7.70) recorded the largest fruit girth. The best performing check, LCA 620 had a fruit girth of 3.45 cm. Notably, 231 accessions exceeded the fruit girth of the check variety.

Fruit diameter also showed substantial variation among the genotypes, ranging from 0.621 to 3.215 cm with a mean value of 1.062 cm. The smallest fruit diameters were observed in CH495 Sel-3 (0.621 cm), CH803 Sel-1 (0.633 cm) and CH124 Sel-2 (0.649 cm), while the largest fruit diameter were recorded in CH430 Sel-2 (3.215 cm), CH869 Sel-1 (2.905 cm), and CH430 Sel-2 (2.320 cm). The best performing check, LCA 620, had a fruit diameter of 0.966 cm, and 273 genotypes recorded higher fruit diameter than the check.

Pedicel length showed substantial variation among the genotypes, ranging from 1.17 to 5.20 cm, with a mean value of 2.53 cm. The best performing check, LCA620, recorded a pedicel length of 3.44 cm. The chilli genotypes CH639 Sel-1 (1.17 cm), CH582 Sel-1 (1.23 cm) and CH688 Sel-1 (1.30 cm) had the shortest pedicel lengths, while CH336 Sel-2 (5.20 cm), CH311 Sel-2 (4.83 cm), and CH655 Sel-1 (4.40 cm) exhibited the longest pedicels. Overall, 26 genotypes displayed pedicel lengths exceeding that of the check variety, LCA620.

A wide range of variability was observed among the genotypes for pedicel diameter, ranging from 0.114 to 0.623 cm, with an average of 0.249 cm. The best-performing check, LCA620, had a pedicel diameter of 0.279 cm. Among the germplasm selections, CH793 Sel-1 (0.114 cm), CH446 Sel-1 (0.124), CH495 Sel-3 (0.134 cm) and CH608 Sel-1 (0.134 cm) exhibited the smallest pedicel diameters. In contrast, CH430 Sel-1 (0.623 cm), CH399 Sel-2 (0.539 cm), CH430 Sel-2 (0.477 cm) and CH398 Sel-1 (0.465 cm) displayed the largest pedicel diameters. Remarkably, 128 accessions recorded pedicel diameters greater than that of the check variety, LCA620.

A broad range of variability was observed in the weight of ten fruits across the genotypes, with values spanning from 2.50 to 270.0 g and a mean value of 31.82 g. The highest fruit weight among the checks was recorded by LCA620 at 22.43 g. The lowest fruit weights were observed in CH691 Sel-1 (2.50 g), CH803 Sel-1 (4.167 g), CH120 Sel-2 (5.0 g), and CH688 Sel-1 (6.0 g).

Conversely, the highest fruit weights were recorded in CH869 Sel-1 (270.0 g), CH411-A Sel-1 (180.0 g), CH398 Sel-1 (151.7 g) and CH430 Sel-2 (120.0 g). Overall, 321 genotypes outperformed the check variety, LCA620, in terms of fruit weight, indicating substantial potential for yield improvement. Estimation of genetic variability, heritability and genetic advance.

Table 3 summarizes key genetic parameters, including the phenotypic coefficient of variation (PCV), genotypic coefficient of variation (GCV), broad-sense heritability (H²), and genetic advance as a percentage of the mean (GAM) for all quantitative traits. Among these traits, days to 50% flowering (DFF) and days to first fruiting (DTFF) displayed moderate values for both PCV and GCV, with DTFF recording the lowest variability. In contrast, fruit length (FL), fruit diameter (FD), fruit girth (FG), pedicel length (PDL), pedicel diameter (PDD), and fruit weight (FW) exhibited high PCV and GCV values, with fruit weight showing the highest variability.

High heritability (H²) estimates were observed for all traits, with fruit length showing the highest value (96.82%). Additionally, all eight quantitative traits exhibited high GAM values, indicating substantial potential for genetic improvement through selection.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on all eight quantitative traits across 470 chilli germplasm selections. PCA reduces a large set of correlated variables into a smaller number of uncorrelated variables, referred to as principal components, while retaining most of the variation present in original dataset [23]. After identifying key traits contributing to variability among genotypes, component loadings were calculated to reveal the underlying data structure (Table 4).

An Eigenvalue was associated with each principal component, representing the proportion of total variance explained, and each eigenvalue corresponded to an eigenvector describing the contribution of individual traits to that component. A Scree plot illustrating the eigenvalues of the principal components was used to visualize this information (Figure 1A). In the present study, the first three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3), each with eigenvalues greater than 1, collectively accounted for 81.4% of the total variation. Among these, PC1 explained 38.9% of the variability observed across all genotypes, PC2 accounted for 24.9%, and PC3 contributed 17.6%.

The principal component analysis (PCA) results the contribution of individual morphological traits to different principal components (PCs), which represent new composite axes summarizing overall phenotypic variation (Table 4). PC1 was primarily associated with fruit size and yield related traits, as indicated by high loadings for fruit diameter (FD), fruit girth (FG), and fruit weight (FW), suggesting that this component captures the major variation related to fruit size and yield potential.

PC2 was predominantly influenced by days to 50% flowering (DFF) and days to first fruiting (DTFF), with high loadings of 0.916 and 0.935, respectively. This component therefore captures the variability associated with the timing of key developmental stages and can be interpreted as a temporal axis, representing earliness or lateness in flowering and fruiting among genotypes.

In contrast, PC3 was mainly influenced by fruit length (FL) and pedicel length (PDL), indicating a component associated with fruit and pedicel dimensional traits. PC4 and PC5 exhibited relatively weaker trait loadings, suggesting that they account for minor variation or more complex trait interactions. Overall, these trait loadings across PCs help identify the principal factors underlying morphological diversity among the evaluated chilli genotypes.

The PCA biplot depicting the relationship between PC1 and PC2, which together accounted for 63.5% of the total variance, highlighted the contribution of distinct genotypes and morphological traits in understanding variation between chilli accessions. As discussed earlier, the direction and magnitude of trait vectors in the biplot reflected both positive and negative association between the traits.

Days to 50% flowering (DFF) showed a highly positive correlation with days to first fruiting (DTFF), while both traits are negatively correlated with fruit girth (FG) and fruit weight (FW). In contrast, fruit diameter (FD) and fruit length (FL) exhibited strong positive correlation and both traits were positively correlated with pedicel length (PDL), pedicel diameter (PDD), fruit weight (FW), and fruit girth (FG).

Figure 1B presents a PCA biplot that integrating chilli accessions and agro-morphological traits. The angles between trait vectors in the biplot reveal the nature of their relationships: smaller angle indicate a positive association, angles close to 90° indicate week or no correlation, and angles approaching 180° denote negative correlations. This visualization categorizes accessions based on their association with specific traits and highlights the relative importance of individual characteristics.

The spatial distribution of accessions reflects their clustering or dispersion the analyzed variables, with closely positioned accessions indicating greater similarity. Several trait relationships are clearly evident from the biplot. A strong positive correlation, as indicated by their narrow inter-vector angle. Similarly, fruit diameter (FD) and fruit girth (FG) were positively associated, while fruit length (FL) and pedicel length (PDL) also formed a small angle, suggesting a strong positive correlation. Overall, the PCA biplot provides valuable insights into trait interrelationships and their impact on the clustering patterns and diversity of chilli accessions.

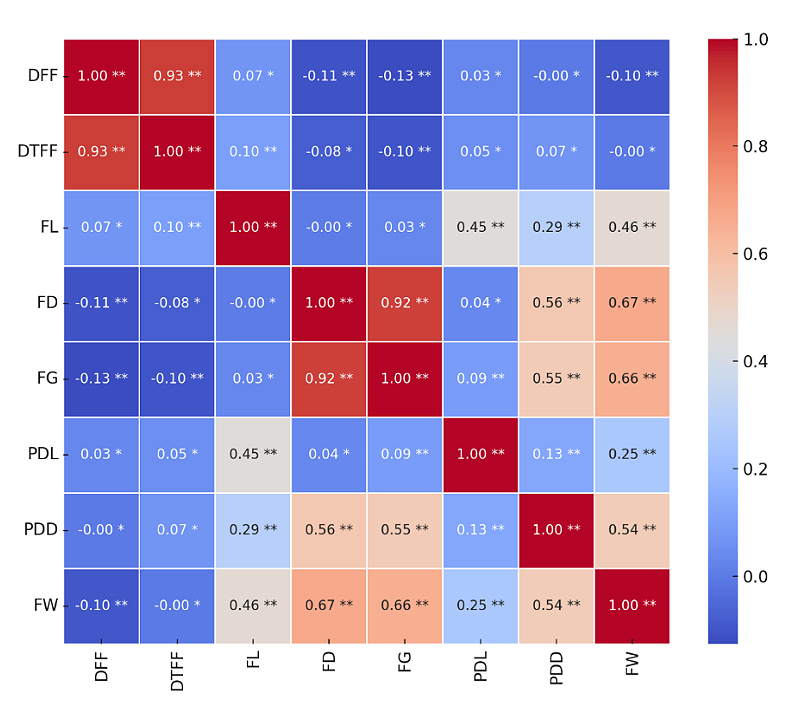

The correlation matrix of eight quantitative traits, computed using the Pearson correlation coefficient, is presented in Figure 2. Days to 50% flowering (DFF) exhibited a very strong positive significant correlation with days to first fruiting (DTFF) (r = 0.93), while showing very weak but significant negative correlation with fruit diameter (FD; r = -0.11), fruit girth (FG; r = -0.13) and fruit weight (FW; r = -0.10). Days to first fruiting showed a very weak positive significant correlation with fruit length (FL; r = 0.10) and a very weak negative significant correlation with fruit girth (r = -0.10).

Fruit length (FL) displayed a moderate positive and significant correlation with both pedicel length (PDL; r = 0.45) and fruit weight (FW; r = 0.46), as well as a weak positive correlation with pedicel diameter (PDD; r = 0.29) and days to first fruiting. Fruit diameter (FD) and fruit girth (FG) showed a very strong positive significant correlation (r = 0.92). Both traits also exhibited moderate positive correlation with pedicel diameter, strong positive correlations with fruit weight and very weak negative correlations with fruit weight, and very weak negative correlations with days to 50% flowering.

Pedicel length (PDL) exhibited a very weak positive correlation with fruit girth and pedicel diameter, and a weak but significant positive correlation with fruit weight (r = 0.25). Pedicel diameter (PDD) had a moderate positive and significant correlation with fruit weight (r = 0.54).

Figure 2. Correlation matrix of quantitative traits where; DFF: days to 50% flowering, DTFF: days to first fruiting, PDL: pedicel length (cm), PDD: pedicel diameter (cm) (PDD), FL: fruit length (cm), FD: fruit diameter (cm) (FD), FG: fruit girth (cm) and FW: fruit weight (g). * = non-significant (p ≥ 0.05); ** = Significant (p < 0.05).

Figure 2. Correlation matrix of quantitative traits where; DFF: days to 50% flowering, DTFF: days to first fruiting, PDL: pedicel length (cm), PDD: pedicel diameter (cm) (PDD), FL: fruit length (cm), FD: fruit diameter (cm) (FD), FG: fruit girth (cm) and FW: fruit weight (g). * = non-significant (p ≥ 0.05); ** = Significant (p < 0.05).

Cluster analysis based on eight quantitative traits categorized all 470 chilli genotypes into two major clusters at a linkage distance of 25. At a lower distance of 15, the genotypes were further classified into four distinct clusters (Cluster I–IV) (Figure 3). The cluster-wise mean values for all quantitative traits are presented in Table 5.

Cluster I, the smallest cluster, comprising 65 genotypes and was distinguished by the highest mean value for fruit length (9.13 cm), fruit diameter (1.329 cm), fruit girth (4.46 cm), pedicel length (3.00 cm), pedicel diameter (0.315 cm), and fruit weight (64.9 g). The days to 50% flowering and days to first fruiting in this cluster exhibited moderate values.

Cluster II, consisting of 76 genotypes, was characterized by late flowering (41.16 days), and late fruiting (47.6 days), along with the lowest mean values for fruit diameter (1.001 cm), fruit girth (3.31 cm), and fruit weight (24.0 g). The remaining traits, including fruit length, pedicel length, and pedicel diameter, showed moderate values.

Cluster III comprised 71 genotypes and was characterized by early flowering (24.39 days) and early fruiting (32.3 days), along with the shortest mean fruit length (5.86 cm) and the smallest pedicel diameter (0.232 cm) among all clusters. Other traits, such as fruit diameter, fruit girth, pedicel length and fruit weight, displayed moderate values.

Cluster IV, the largest cluster, included 258 genotypes. The cluster exhibited the lowest mean pedicel diameter (2.43 cm), while the remaining seven traits showed moderate mean values.

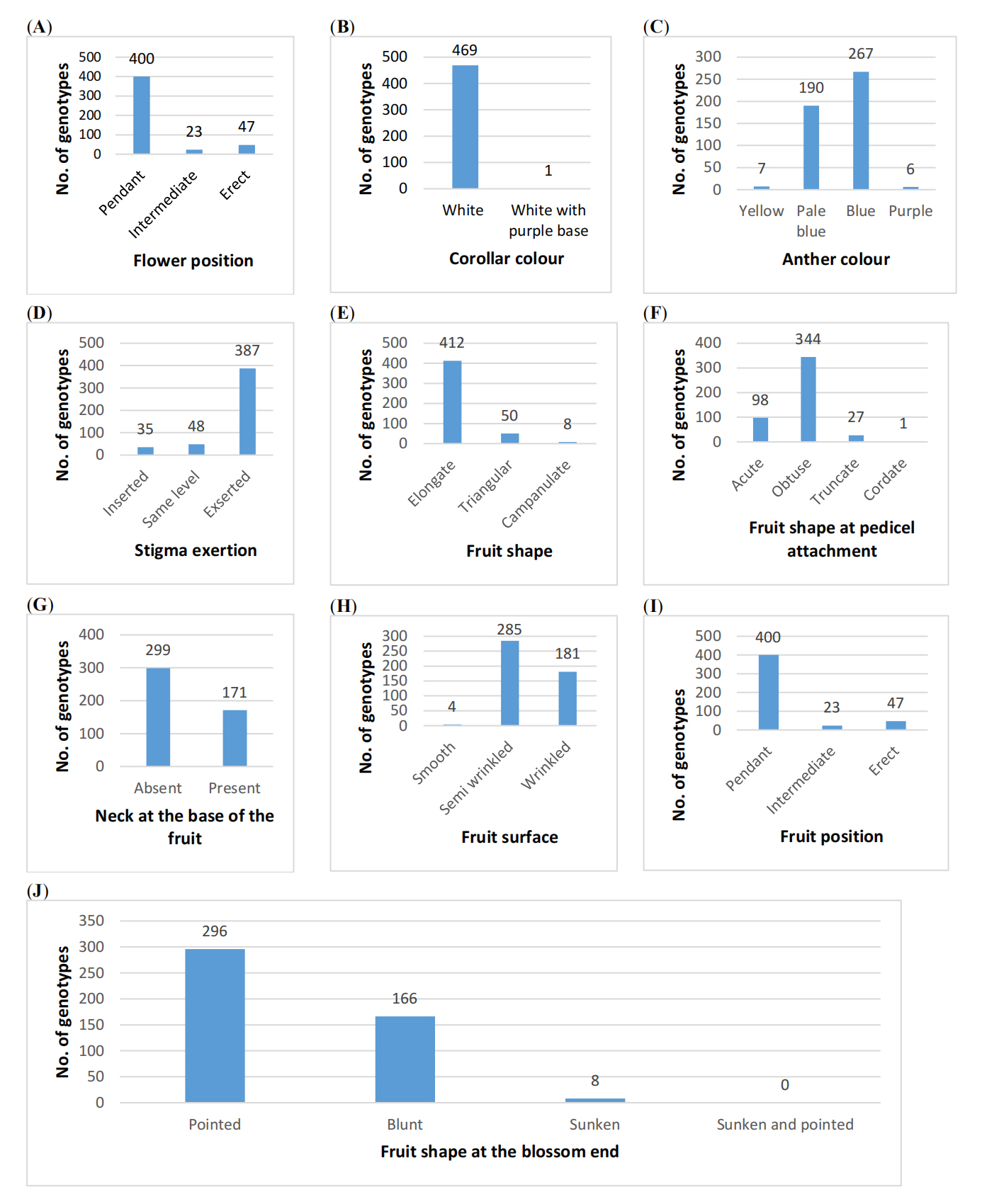

Qualitative traits were recorded at appropriate growth stages to ensure the full expression of each trait. The descriptors, descriptor states, and frequency distributions of these traits are presented in Table 6. Accordingly, qualitative traits were assessed at the flowering and fruiting stages, as described below.

Flowering stage:The qualitative traits studied at the flowering stage included flower position (FP), corolla colour (CC), anther colour (AC), and stigma exertion (SE). The majority of genotypes (85.1%) exhibited pendent flowers, while 4.9% had intermediate and 10.0% showed erect flower positions (Figure 4). Corolla colour was predominantly white (99.8%), with only 0.2% of genotypes displaying white corollas with a purple base.

Anther colour exhibited considerable variation, with 56.8% of flowers showing blue anthers, 40.4% pale blue, 1.5% yellow and 1.3 % purple. With respect to stigma exertion, 82.3% of genotypes exhibited exserted stigmas, while 10.2% had stigmas at the same level, and 7.4% displayed inserted stigmas.

Fruiting stage:At the fruit formation and maturation stages, qualitative traits such as fruit shape (FS), fruit shape at pedicel attachment (SPA), neck at the base of the fruit (NBF), fruit shape at the blossom end (FSBE), fruit surface (FSRF) and fruit position (FRP) were recorded for all genotypes. Elongated fruit shape predominated (87.7%), followed by triangular (10.6%) and campanulate (1.70%) forms.

Considerable variation was observed in fruit shape at pedicel attachment, with 344 (73.2%) exhibiting obtuse attachment, 98 (20.9%) acute, 27 (5.70%) truncate and one genotype (0.20%) cordate. For the neck at the base of the fruit, 63.6% of accessions lacked a neck, while 36.4% exhibited a neck.

Regarding fruit shape at the blossom end, 62.3% of the genotypes were pointed, 35.3% blunt, 1.7% sunken, and 0.4% sunken with a pointed tip. Fruit surface texture analysis revealed that 60.6% genotypes were semi-wrinkled, 38.5% wrinkled, and only 0.9% smooth. Fruit position was predominantly pendent, while 10.0% of genotypes exhibited erect fruit position and 4.9% intermediate orientations (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 4. Variation in qualitative traits at flowering and fruit formation stage among 470 germplasm selections of chilli pepper (X-axis represents number of genotypes; Y-axis denotes the descriptor states corresponding to each trait). (A) Flower position (B) Corolla colour (C) Anther colour (D) Stigma exertion (E) Fruit shape (F) Fruit shape at pedicel attachment (G) Neck at the base of the fruit (H) Fruit surface (I) Fruit position (J) Fruit shape at the blossom end

Figure 4. Variation in qualitative traits at flowering and fruit formation stage among 470 germplasm selections of chilli pepper (X-axis represents number of genotypes; Y-axis denotes the descriptor states corresponding to each trait). (A) Flower position (B) Corolla colour (C) Anther colour (D) Stigma exertion (E) Fruit shape (F) Fruit shape at pedicel attachment (G) Neck at the base of the fruit (H) Fruit surface (I) Fruit position (J) Fruit shape at the blossom end

Specific genotypes exhibiting superior performance were identified for fruit length, fruit weight, earliness, fruit girth, fruit diameter, pedicel length, and pedicel diameter (Table 7). Genotypes such as CH869 Sel-1, CH191-A Sel-1, and CH399 Sel-2 were identified as long-fruited types suitable for paprika production, while CH869 Sel-1, CH411-A Sel-1, and CH398 Sel-1 showed high fruit weight, indicating high yield potential. Early flowering genotypes, including CH132 Sel-1, CH219 Sel-1, and CH854 Sel-1, are suitable for short-duration cropping systems. Genotypes CH430 Sel-1 and CH430 Sel-2 performed well for fruit girth, diameter, and pedicel traits, making them suitable for processing and ease of harvest. Notably, CH869 Sel-1 emerged as an outlier in PCA analysis, indicating high overall diversity and potential utility as a parent in breeding and crossing programmes.

Agro-morphological characterization is an essential component of chilli improvement programmes [24], as it enables the identification of genotypes with higher yield potential, stress tolerance, and quality traits, thereby supporting effective parent selection and the use of untapped germplasm resources [24,25]. In line with this objective, our study assessed phenotypic diversity among chilli germplasm selections to strengthen future breeding and conservation strategies.

Substantial variations were observed in days to 50% flowering (19 to 56 days) and days to first fruiting (26.10 to 70.77 days), indicating the presence of considerable genetic variations among the evaluated genotypes. The results of the present study are consistent with previous reports, such as Ridzuan et al. [27], who noted a range of 20.38 to 34.5 days for 50% flowering in 14 genotypes of chilli, while Chattopadhyay et al. [28] reported higher values ranging from 30.33 to 109.00 days. Such wide variation reflects the diverse genetic backgrounds of the evaluated genotypes and their differential responses to the growing environment. These traits directly influence earliness, an attribute important for short-duration and intensive cropping systems. The presence of early-, mid-, and late-flowering types in the present collection provides considerable scope for breeding cultivars suited to specific production niches.

Fruit related traits also displayed considerable diversity in the evaluated material. Wide ranges were observed for fruit length (1.90 to 13.70 cm), fruit diameter (0.621 to 3.215 cm), fruit girth (1.29 to 10.97 cm), pedicel length (1.17 to 5.20 cm) and pedicel diameter (0.114 to 0.623 cm). These finding are consistent with earlier reports [28-31]. Chattopadhyay et al. [28], reported green fruit lengths ranging from 2.93 to 14.97 cm. which closely align with the present observations. Similar findings were also reported by other studies [29]. Anani et al. [30] observed fruit widths between 0.433 to 1.711 cm. While, Yatung et al. [31] reported fruit diameters varying from 0.46 to 2.05 cm. Anani et al. [30] further documented pedicel lengths of 2.25 to 3.23 cm and pedicel diameter ranging from 0.19 to 0.31 cm in chilli genotypes.

The wide variability observed in fruit and pedicel traits underscores the substantial genetic diversity present among the studied genotypes, offering valuable opportunities for selecting desirable types in breeding programmes. Medium-sized fruits are generally preferred over very long fruits, because they tend to remain intact during storage, while longer fruits are more prone to breaking at the distal ends [32]. Fruit size and shape therefore play a critical role in determining market preference and processing suitability.

Promising germplasm selections exhibiting the longest fruits included CH869 Sel-1 (13.70 cm), followed by CH191-A Sel-1 (13.57 cm), CH399 Sel-2 (13.17 cm), CH380 Sel-2 (11.83 cm) and CH397 Sel-1 (11.80 cm). Genotype with longer fruits were predominantly associated with paprika-type chillies. Several germplasm selections, including CH318 Sel-2, CH494 Sel-1, CH681 Sel-2 (6.40 cm), CH103 Sel-1 and CH332 Sel-2 (6.43 cm), exhibited fruit lengths close to the average. In contrast, the shortest fruits were observed in genotypes CH479 Sel-3 (1.90 cm), CH490 Sel-1 (2.17 cm), CH484 Sel-2 (2.23 cm), CH500 Sel-1 (2.30 cm) and CH201 Sel-1 (2.77 cm). Depending on specific breeding objectives, these genotypes may be utilized for the development of new chilli varieties.

All qualitative traits showed wide variability among the chilli genotypes, which is consistent with earlier reports [29,33,34]. Flower position showed considerable variation, with the majority of genotypes exhibiting a pendent orientation, while only a few displayed erect or intermediate flower positions. In addition, 99.8% of the genotypes had white corollas, with only one genotype showing a white corolla with a purple base. Similar observations were reported by Lahbib et al. [35], who found that all evaluated genotypes had white flowers.

Flower position is particularly important for chili breeders, as it plays a role during the hybridization process and in assessing the potential for cross-contamination [36]. Furthermore, corolla colour (flower colour) has been reported to influence pollination behavior [26]. Stigma position was predominantly exserted among the genotypes, and Rahevar et al. [37] also reported comparable variation in stigma exertion in chilli germplasm.

The majority of fruits exhibited an elongated shape (87.7%), with 10.6% were triangular and 1.7% were campanulate. Gurung et al. [33] similarly reported predominance of elongated fruits, along with triangular, almost round and blocky types and comparable level of diversity were also noted [38]. Fruit shape is an important distinguishing characteristic in chilli, as it aids in the classification and differentiation of pepper varieties [39].

Considerable variation was also observed in fruit shape at the pedicel attachment, which was predominantly obtuse, and in fruit shape at the blossom end, ranging from pointed (62.3%) to blunt (35.3%), sunken (1.70%) and rare sunken with a pointed tip (0.4%). Additionally, the absence of the neck at the base of the fruit was observed in 433 genotypes. Similar patterns of variation have been reported in earlier studies [34,35,37]. Semi-wrinkled fruit surfaces were most common (60.6%).

Most genotypes showed a pendent fruit position (85%), followed by erect (10%) and intermediate (4.9%) orientations. Flower and fruit positions are generally consistent, allowing one trait to be inferred from the other, a trend also reported previously [33,37]. As farmer preferences for fruit orientation differ across regions [40], this diversity is particularly valuable for breeding region-specific cultivars.

Assessment of genetic variability and heritability is essential for determining the potential effectiveness of selection for important traits [41]. In our study, fruit weight exhibited the highest phenotypic and genotypic coefficient of variation (PCV and GCV), followed by fruit length, pedicel diameter, fruit diameter, fruit girth and pedicel length. In contrast, days to 50% flowering showed moderate variability compared with days to first fruiting. Similar trends have been reported by earlier studies [27,28], which also observed high PCV and GCV values for traits such as fruit weight, fruit length, fruit girth and number of fruits per plant in chilli.

Broad-sense heritability (H2) was high for all evaluated traits, with fruit length and pedicel diameter recording the highest values, thereby confirming previous findings [28]. The combined presence of high variability and high genetic advance indicates strong additive gene action, suggesting that selection for traits such as fruit weight, fruit length, and pedicel diameter would be effective for the development of improved chilli cultivars [28].

In the present study, the first three principal components (PC1-PC3) accounted for 81.4% of the total phenotypic variation, which is comparable to the 75% variation reported by Lahbib et al. [35] in chilli. PC1, explaining 38.9% variation, was primarily influenced by fruit girth (0.882) and fruit diameter (0.881). PC2, which explained 24.9% of the variation, was largely associated with days to first fruiting (0.935) and days to 50% flowering (0.916), while, PC3, accounting for 17.6% of the variation, was mainly influenced by fruit length (0.718) and pedicel length (0.688).

These results align with Anani et al. [30], who reported plant height, fruit width, and fruit number as major contributors to phenotypic variation. The PCA biplot revealed a wide dispersion of genotypes, indicating significant morphological diversity, which can be effectively exploited for the selection of desirable traits in chilli breeding programmes [35,42].

Correlation analysis of quantitative traits in chilli unveiled a strong and significant positive correlation between days to 50% flowering and days to first fruiting, as previously reported [27,30]. This positive association suggests that early flowering is closely linked to early maturity, thereby facilitating the development of short-duration varieties and enabling farmers to harvest earlier and achieve higher market value [43].

On the other hand, days to 50% flowering showed a weak but significant negative correlation with fruit diameter, fruit girth and fruit weight, indicating that delayed flowering may adversely affect fruit size and yield. Consequently, selection of early-flowering genotypes is likely to enhance fruit weight and overall productivity. Ahmed et al. [44] similarly reported a significant negative correlation between days to 50% flowering and fruit weight.

Additionally, a significant positive correlation between fruit length and fruit weight was observed, indicating that longer fruits tend to be heavier, consistent with the findings of Ahmed et al. [44]. Fruit length and pedicel diameter were significantly positively correlated, indicating that larger fruits tend to have thicker pedicels to support their weight. This relationship is consistent with findings by Anani et al. [30] and Setiamihardja and Knavel [45]. In addition, fruit diameter was positively corelated with pedicel diameter and fruit weight, confirming that larger fruits tend to possess stronger pedicels and higher weight, as also observed by Yatung et al. [31].

Hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), effectively categorized the 470 chilli germplasm selections into four major clusters at a distance threshold of 15. This clustering pattern highlights the presence of substantial genetic variability between the evaluated genotypes and, can be instrumental in selecting desirable chili phenotypes for breeding programmes. Each cluster exhibited a distinct group means and varied in number of constituent genotypes.

Comparable clustering patterns have been reported previously, as Lahbib et al. [35] grouped 11 chilli accessions into four clusters using HCA at a distance of 0.87. Similarly, Ridzuan et al. [27] classified 14 chilli germplasm accessions into eight distinct clusters based on quantitative traits, thereby facilitating effective the differentiation of genotypes within the population.

Future ScopeFuture research should capitalize on the diverse chilli germplasm identified in this study to develop short-duration, high-yielding, and market-preferred cultivars. Integrating marker-assisted selection and trait-specific breeding approaches can efficiently incorporate key attributes, such as early flowering, optimal fruit size, and weight. Furthermore, multi-location trials are recommended to assess genotype stability and environment adaptability. Additional biochemical and molecular characterization of promising lines can facilitate the identification of trait-linked markers, thereby enabling precision breeding. Together, these strategies will accelerate the development of improved cultivars, align with farmer preferences, and boost chilli productivity and market value.

The evaluation of 470 Capsicum annuum L. genotypes revealed a well-structured and previously under-documented spectrum of agro-morphological diversity within the Indian National Genebank. In addition to assessing variability, our findings identified key traits and superior genotypes that can directly strengthen breeding pipelines targeting yield, earliness, and fruit-related attributes. Multivariate analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), provided insights into the extent of diversity and relationships among genotypes, thereby enabling more informed parent selection and trait-focused pre-breeding efforts. Furthermore, the findings offer actionable insights for genebank management, particularly in germplasm curation, duplicate identification, and gap-filling, ultimately strengthening strategies for the conservation and effective utilization of chilli genetic resources.

The following supplementary materials are available online. Table S1. Stages at which quantitative traits were measured; Table S2. Details of descriptors and descriptor states and stage of recording observation for qualitative traits recorded in the study; Table S3. Mean values of eight quantitative traits of chilli germplasm selections; Figure S1. Variability in morphological traits among Capsicum annuum germplasm selections.

All data and materials mentioned in this article are available.

DDD, HM, VPS did data curation, original draft preparation. DDD, GJA, GM, SDM, DT did statistical analysis. CDP, HB provided diverse chilli material and project administration. RKG, project administration and supervision. GPS supervision. JCR, VKS critical review, revision, and resources. AS, MM, ABG, AKS, VKS conceived and designed the experiments, study supervision, results interpretation. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version before submission.

The authors declare that there are Consent for publication. The authors declare that there is no conflict of commercial interest related to this paper.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors acknowledge the support received from ICAR-NBPGR, New Delhi. The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, India Office, New Delhi 110012, India in carrying out these studies. The authors gratefully acknowledge Sonal Dsouza of the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, New Delhi, for her English language editing services.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

Deepika DD, Sharma V, Mehta G, Mehta H, Devi Pandey C, Gaikwad AB, et al. Dissecting the Genetic Diversity of Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.): A Germplasm-Wide Analysis of Agro-Morphological Traits. Crop Breed Genet Genom. 2026;8(1):e260003. https://doi.org/10.20900/cbgg20260003.

Copyright © Hapres Co., Ltd. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions